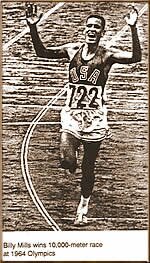

Billy Mills

(1928- )

Click for a larger image

Billy Mills was the first American to win a gold medal in a distance race in the Olympics. Against tremendous odds he set a world record during the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, Japan, becoming an instant celebrity in the process. William M. Mills was born on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in 1938. His mother died when he was seven and his father died six years later, leaving eight orphaned children. His father had boxed for a living, but after his death there was no one to support the family. As was often the custom, Billy was sent away to a Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school.

He entered Haskell Indian School in Lawrence, Kansas. Taking after his father, he tried out for the boxing team. Although he was only five feet, two inches tall and weighed a mere 104 pounds, he joined the football team. He was attracted to the vigorous discipline of football and felt, at that time, that track was a “sissy” sport. But when he eventually turned to track, he discovered that it was extremely demanding. He soon began to develop physical endurance and strength through robust training. The physical and mental discipline it required, along with his natural abilities, helped him develop into a successful competitive runner. He won the Kansas State two-mile cross country championship three years in a row and took the state mile championship as a junior and senior. When he graduated from high school, the University of Kansas awarded him a full athletic scholarship.

In college, Mills often felt lonely and isolated. He had little contact with his scattered brothers and sisters, and no one took a special interest in him or his running. Despite the lack of attention that he received individually, Mills set a conference record of 31 minutes in his first 10,000-meter race and became the Big Eight cross-country champion during that time. His team won the National Track Championships two years in a row while he was a junior and senior. Still, he did not gain prominence or recognition as a runner.

After trying and failing to qualify for the Olympic team, he became discouraged, finishing poorly in races and occasionally dropping out of events. In an interview for Contemporary American Indian Leaders, he recalled this period: “I didn’t realize then, but it was because of my attitude. I just didn’t want to make the effort. I wasn’t interested and because I wasn’t, it was impossible for me to win. I blocked myself off from winning.” Just before graduation, Billy married his college sweetheart; shortly thereafter, he accepted an officer commission from the U.S. Marine Corps.

Some of his fellow Marines were aware of his extraordinary athletic talent, and one of them encouraged him to begin running again. He began training and won the interservice 10,000-meter race in Germany with a time of 30:08. Also, concentrating on the one-mile race, he got his time down to 4:06 minutes.

The Marines sent Mills to Tokyo, Japan, to compete in the Olympic Games in 1964. This was a unique opportunity for the young Sioux athlete. He entered the games as a complete unknown, with odds of 1,000 to 1 against him—no American had ever won a distance race in the Olympics. Just minutes before the race, the American coach was calculating the possibilities that any of his athletes would place in the race. Billy Mills’s name was not even mentioned.

He began the race with silent determination, and by the last 300 meters he was actually leading the other 36 world-class track stars. Suddenly, he was pushed by another runner and he stumbled, dropping 20 yards behind. In the next few seconds he charged ahead, capturing one of the major upsets in Olympic history. He won the race in 28:24.4, establishing a new Olympic record and winning the gold medal. “My Indianness kept me striving to take first and not settle for less in the last yards of the Olympic race,” he said in his interview. “I thought of how our great chiefs kept on fighting when all of the odds were against them as they were against me. I couldn’t let my people down.”

The world was astonished at Mills’s run and he became an instant international hero. Yet he remained modest and dignified. The president of the International Olympic Committee commended Mills for his ability to respond to pressure, saying never in 50 years had he seen a better reaction to such circumstances.

The honor of successfully representing the United States meant a lot to Mills, but his most cherished tributes came from his own Lakota people in the form of traditional gifts. He became a role model to generations of young people growing up in Pine Ridge. He traveled all over the world, speaking in over 51 countries. He always emphasized his tremendous desire to win as well as his Indianness. “I wanted to make a total effort, physically, mentally, and spiritually,” he insisted. “Even if I lost, with this effort I believed that I would hold the greatest key to success.”

His story was admired around the world, and a movie—Running Brave—was filmed about his early hardships, his determination, and his Olympic victory. An honored spokesperson for Indian athletes, Mills remarked: “[Other Indians] have ability far greater than mine, and if they are given the opportunity to explore and develop their talents, they can achieve any personal and educational goal they choose, especially if they make this total physical, mental and spiritual effort.”

After the Olympics, Billy Mills continued to train and to run, setting another record in the six-mile race. At this time he lived in California with his family and sold insurance for a living. He tried out for the 1968 Olympic Games, but because of a technicality regarding his application form, he was denied a place on the team. Several other Olympians voiced their objection, but he was not reinstated. He ran in the qualifying 5,000-meter trial, even though he was not a contestant for the team, finishing 13 seconds ahead of the fastest runner who qualified for the games.

For a time he felt bitter and discouraged. It seemed that politics had kept him out of the 1968 Olympics. Then, as he had so often, he put the bitterness behind him and went on with his life. “A man can change things,” he explained in his interview. “A man has a lot to with deciding his own destiny. I can do one of two things—go through life bickering and complaining about the raw deal I got, or go back into competition to see what I can do.” He has devoted a great deal of his time to Indian causes, speaking out about the benefits of physical discipline and self-esteem. In 1977 he was named one of ten outstanding young men of the United States by the U.S. Junior Chamber of Commerce. In 1994 he published a book, Wokini: A Lakota Journey to Happiness and Self-Understanding.

Source: Native North American Biography edited by Sharon Malinowski and Simon Glickman