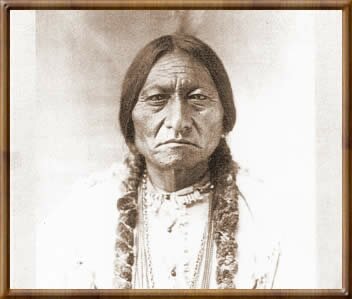

Tatanka Iyotanka (Yotanka), a Hunkpapa Sioux leader, was born on March 31, 1834 at Many Caches on the Grand River near Bullhead, South Dakota. He was the son of Tatanka Psica, Jumping Badger (sometimes known as Jumping Bull or Sitting Bull), a Sioux war chief. In his early years, the lad was known as Hunkesni, “Slow,” but soon became more widely acclaimed for his courage and strength in battle. He was head of the Strong Hearts, a warrior society, and became an important medicine man and tribal councilor, although he was never a true “chief” of his people.

Sitting Bull was implacably opposed to the White man’s continual encroachment on Indian land. Always something of a militant, in the 1860s he was active in the Plains Indian wars, and his camp became a meeting place for many tribes in the area who staunchly opposed the Whites. In 1868, following Red Cloud’s war, the United States government signed a treaty guaranteeing the Plains Indians a reservation north of the Platte River, plus the right to hunt buffalo off the reservation. The territory included Paha Sapa (the Black Hills), an area traditionally regarded as sacred by the Sioux. But the authorities did little to prevent the Whites from coming onto the reservation; and when gold was discovered in 1874, thousands of prospectors poured onto the land, ignoring land ownership and Indian rights. The Indian people were particularly incensed by the desecration resulting from miners’ digging into the sacred area, and in the following year, Sitting Bull, as head of the Sioux war council, made plans with the Cheyenne and Arapaho to force them out.

Recognizing the dangerous situation, the government ordered all Indians to return to their reservations by the end of January 1876. When the Indians defied the order, the Army was moved into the area; the Indians also gathered their own forces and upwards of 3,000 warriors readied themselves for the coming battle. In early June, Sitting Bull performed a Sun Dance to determine the outcome; he danced for more than a day and a half before receiving a vision. In his vision he saw many White soldiers falling upside down from the sky into the Indian camp; this was clearly a good sign and the Indians were confident of victory.

On June 16, at the Battle of the Rosebud, Crazy Horse defeated the troops under General George Crook, but the vision was not fulfilled until June 25, when General George Custer and several hundred soldiers were wiped out when they attacked the Indian camp on the banks of the Little Bighorn. Aroused and humiliated by these and other defeats, the Army concentrated on a relentless pursuit of the Sioux. Many surrendered, but Sitting Bull and his followers escaped into Canada. While they were not welcomed by the Canadians nor helped through the severe winter, their unwilling hosts did resist United States efforts to have the Indians returned. Many Indians died, or went back to the reservation during the bitter winter, and finally on July 19, 1881, Sitting Bull and the remaining holdouts surrendered at Fort Buford, Montana. He was imprisoned for two years before being allowed to return to Standing Rock; but by that time he had become a legend to the Whites, and in 1885 was the star attraction in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show which traveled throughout the East.

Sitting Bull’s heart remained with the Indian needs. He trusted no Whites, and expected only deceit and lies from them, especially in any treaty negotiation, for that is all that he had ever experienced. When the government tried to break up the Sioux reservation, he cautioned his people against being tricked again into selling their heritage. But the Federal Commission, sent out in 1889 to negotiate the matter, was able to bypass his influence by meeting individually with tribal leaders, or in very small groups away from tribal council meetings.

This divide-and-conquer technique had long been successful in dealing with Indians, and Sitting Bull was perhaps the last Sioux leader whose influence was strong enough to unite the people under one person. When he enthusiastically supported the adoption of the Ghost Dance movement which had just been introduced by Kicking Bear, some Indian Agents panicked; they feared that the Ghost Dancers and their strange ceremonies—so highly charged with emotion—would lead to an uprising, not recognizing the essentially pacifistic nature of the movement. Indian Police were sent to arrest Sitting Bull on December 15, 1890, in the hope that this would end the Ghost Dance. In the melee which ensued, Sitting Bull, his son Crow Foot, and several others were shot to death by Red Tomahawk and Bullhead, of the Police group. A few days later, the tragic massacre at Wounded Knee took place, and the Ghost Dance did indeed cease.

Sitting Bull was a man of many dimensions, whose actions aroused as mixed emotions as did his personality. He had several wives—some accounts record nine—of whom perhaps Pretty Plume, Wiyaka-wastewin, and Zuzela are best known. He is said to have sired nine children, among whom Crow Foot and Standing Holy are most frequently mentioned. His intransigence in the face of White aggression, his courage in defending his people, and his refusal to step aside in an impossible struggle, have made him into an almost mythical figure in American history. Among Indian people his organizational ability, medicine power, and willingness to lead have made him a figure of respect, even among some who denigrate him as a glory seeker or for not being a “true chief.”

Source: Great North American Indians by Frederick J. Duckstander