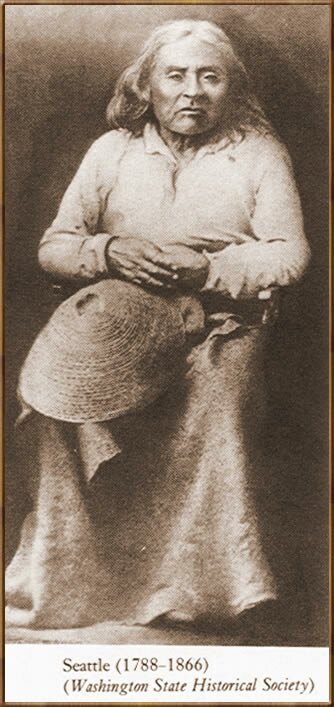

Seattle (1788-1866)

Seattle, more correctly Seathl or Sealth, the chief of the Susquamish, Duwamish, and allied Salish-speaking tribes, was born near the present location of the city named for him. He was the son of Susquamish leader named Schweabe and a Duwamish woman named Scholitza (or Wood-sholitsa); therefore, he is usually regarded as Duwamish. The date of his birth is uncertain; it was sometime between 1786-1790. As a young man, Seathl was an active warrior widely known for his daring. Then he became convinced that peace was preferable to war, largely due to the influence of Catholic missionaries who were coming into the Northwest Territory in the 1830s. In time, he converted to Christianity, taking the name Noah from his favorite biblical character; at the same time, many of his tribesmen also converted.

Following the peak of the California Gold Rush, more Whites came into the Northwest to settle in the Puget Sound region. They were warmly received by the Indians, and in 1852 the name of the local settlement was changed to “Seattle” in honor of the chief.

During this time, however, there was increasing conflict between Indian and White. Some Indians rebelled against the oppressive weight, and were led by Kamiakin and Leschi; but Seathl and his people remained at peace. Finally, in the spring of 1855, Governor Isaac Stevens called a series of councils to try to persuade all of the tribes to move onto reservations which had been set aside for them. The Indians were given a voice in establishing the boundaries of these reservations, and were thereby able to include some of their favorite lands.

Although Seathl was the first to sign the Port Elliott Treaty of 1855 accepting a reservation, he declared, “The red man has ever fled the approach of the White man as morning mist flees the rising sun. It matters little where we pass the remnant of our days. They will not be many. The Indian’s night promises to be dark . . . a few more moons . . . a few more winters.”

The reservations were not readily accepted by many tribes, and warfare continued for over 15 years, until the military superiority of the U.S. Army finally crushed all Indian resistance in the area. Seathl had continuously refused to let his people become enmeshed in the conflict, realizing that only bloodshed would result, with the certain extinction of his small band. They moved to the Port Madison Reservation and lived in relative peace despite the chaos whirling around them. There he lived in Old Man House, just across from northern Bainbridge Island; this was a “community house,” measuring some 60 x 900 feet—easily the largest Indian-made wooden structure in the region.

In his old age, Seathl asked for and received a small tribute from the citizens of the town named after him—advance compensation against the tribal belief that the mention of a man’s name after his death disturbed his spirit. He died at Port Madison on June 7, 1866 and was buried in the Suquamish Indian cemetery near Seattle. He married twice; his first wife, Ladaila, a Duwamish woman, died after bearing one daughter, Kiksomlo, known as “Angeline.” The second, Oiahl, had three daughters all of whom died young, and two boys, George and Seeanumpkin.

Source: Great North American Indians by Frederick J. Duckstander